Congress acts. Connecticut war on opioids continues.

Connecticut’s ad hoc network of opioid treatment and prevention services can expect about a $6 million increase from a recently approved federal funding bill that includes nearly $1.5 billion for State Opioid Response Grants, a relief to treatment specialists who feared last year that the Trump administration might be stepping back from the state grants.

Officials said Thursday that the grant program, created in 2017 with strong bipartisan support in Congress, will continue with a $500 million increase over the $933 million allotted to states last year and allow the continuation in Connecticut of an evolving array of prevention, outreach, treatment and follow-up support.

“There is really in my view no cause for celebration, more a cause for greatly increased commitment, because that $500 million for the nation as a whole is literally a pittance,” said U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn. “What we really need to do is a massive commitment in the range of $100 billion over 10 years.”

Despite a slight dip nationally in overdose deaths in 2018, the opioid epidemic claimed 1,088 lives in Connecticut last year and continues to kill 130 people every day across the U.S., evidence of a continuing public health threat that demands a sustained and coordinated response, Blumenthal said.

At a press conference Thursday organized by Blumenthal and attended by a dozen treatment experts, there were varying views on how much progress the state has made in developing an integrated system for directing opioid abusers to treatment and supporting them upon a release that for many will lead to an eventual relapse, according to research data.

Shawn Lang, the deputy director of AIDS Connecticut, said the services exist, but finding them still can be difficult.

“There needs to be better coordination around the state, because there is great work happening in lots of different pockets in the state — but you only know about if you know about it,” Lang said. “There needs to be some sort of hub that gathers all that information that we can easily access, so when we get calls from people looking for those resources we can easily refer them and connect them.”

Mark Jenkins, the executive director of the Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Coalition, said the State Opioid Response, or SOR, grants to non-profits and the state Department of Addiction and Mental Health Services is quickly producing an effective network.

His coalition is a non-profit formed in 2014 with a mission to “meet folks where they are at,” bringing training, services and products to neighborhoods, streets and places where they are needed. That includes “care packages” distributed at hospital emergency departments to overdose survivors.

Miriam E. Delphin-Rittmon, the commissioner of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, said her agency is trying to play that role with a live-staffed hotline, 800-563-4086.

The SOR grant program delivered $11.1 million to Connecticut in each of its two full years, plus a $5.8 million supplemental grant in the first year, according to state-by-state data compiled by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Delphin-Rittmon said the new money will be allocated based on assessments of overdose “hotspots” and other data, including demographics. A recent study by the Office of Policy and Management found that more than 50% of fatal overdoses involved people who had been in prison.

Rebecca Allen, the director of recovery support services for CCAR, the Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery, said the SOR grants have allowed her organization to dispatch “recovery coaches” to Connecticut hospitals, helping addiction patients find services and support after overdoses and other medical crises.

They answered 5,000 calls in the past year and more than 8,000 since beginning in 2017. They have a 90% success rate in re-connecting patients to care — an important statistic for an area of medicine where treatment rarely works the first time.

“It doesn’t really happen after a 30-day program,” said Dr. Charles Atkin, a psychiatrist and the chief medical officer at Community Mental Health Affiliates in New Britain. “In fact, over 50 percent of people when they leave a 30 day program will relapse within one week, so we need to be thinking longer term, really understand the disease model of addiction and look at some of the initiatives that are going to move the dials.”

Eighty percent of people trying to kick an addiction will relapse in 12 months, he said.

“If it’s cigarettes or alcohol it’s terrible, but it’s not going to kill you today. But if it’s a bag of $3.50 fentanyl-laced heroin you bought on the streets of New Britain, and you’ve lost your tolerance in a 30-day rehab program, that one or two bags of $3 to $4 dope” can kill, Atkins said.

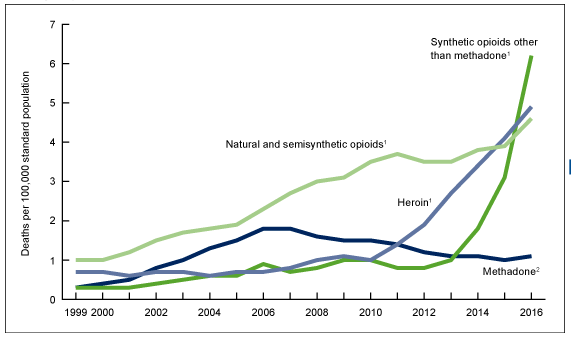

Nationally, a decline in deaths attributed to prescription opioids in 2018 produced the first drop in drug overdose deaths since 1990, according to data released in July 2019. But fatal overdoses from fentanyl and other drugs continued to rise.

Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. After being used to boost the potency of heroin, it is now finding its way to cocaine, particularly crack cocaine, Atkins said.

The ubiquity of fentanyl in street drugs is why naloxone must be readily available wherever opioids are being consumed, the advocates said. Naloxone, sold by the brand name of Narcan, almost instantly negates the effects of an overdose, giving addicts a second chance at recovery.

Jenkins said the number of lives saved with naloxone in Connecticut is hard to quantify, but naloxone distributed by his group has reversed 100 overdoses in Hartford alone in the past year year.

Atkins said the key to recovery is getting people through the critical six months to a year after initial treatment. Allen, who has a master’s degree in public health, concurred. She has been been off heroin for 22 years.

“I share this freely,” Allen said, “because I believe like many of my colleagues standing behind me that breaking stigma around addiction is very necessary.”

Free to Read. Not Free to Produce.

The Connecticut Mirror is a nonprofit newsroom. 90% of our revenue comes from people like you. If you value our reporting please consider making a donation. You'll enjoy reading CT Mirror even more knowing you helped make it happen.

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center

Pathways Drug Rehabilitation Luxury Addiction Treatment & Detox Center